|

|

|

|

|||

|

The Stans

Close your eyes, and think of a globe. Put your imaginary finger on imaginary San Francisco. Now, with your other hand, spin the globe exactly one half turn. You're in Turkmenistan. Uzbekistan is an inch northeast. Kazakhstan an inch north of that - Kyrgyzstan, over to the right. Tajikistan, down.

Now, actually getting to Central Asia - that's a little different.

Ted: "So far everything is fine...except that two bags are missing upon arrival in Moscow. Naturally, there's no indication they will ever turn up in the eastern hemisphere." Before you can even get to Central Asia, there are a number of tribulations - tests, if you prefer - that you have to get through. It's a little like Aeneas, descending to the Underworld - except, instead of tricking the haunted boatman and subduing the three-headed dog, you have to make it through the Moscow airport.

Ted: "Well, if there had to be a casualty, I'd rather it be luggage than people. All things considered, it sucks, but it's not the worst case I've seen." This is Ted Rall, nationally syndicated political columnist, cartoonist, radio talk show host. He's our guide. Our leader. And this whole trip, the whole idea of Stan Trek 2000, was his. Which has one very important repercussion: Ted Rall is to blame. Oh, Ted, and his sidekick. Tracy.

Tracy: "...In this case we have designated Ted as our fearless leader. If everyone gets involved, it's no good for anybody. It screams weakness, it's screams 'Come here and kill me.'" See, this isn't even in the Stans yet. This is still on the way.

Ted: "Don't go to the bathroom without telling me and Tracy. Really. Don't. There are 24 people and at any time, there's been five people taking a dump." To understand "our fearless leader," you have to know two things about him. The first is that he gave that title, "our fearless leader," to himself. He just kind of assumed it. The second is that this: Stan Trek 2000, is going to be his big chance to prove it. To lead us all through the most dangerous part of the world, and come home a hero. Motorcades down Broadway. Tickertape parade. Our undying honor, loyalty, and a willingness to follow him anywhere. That's what these next three weeks are supposed to be. So we cross the tarmac, the River Styx and get on our plane. A few more hours and we're there: Hades. Central Asia. Turkmenistan. Ashgabod.

Stan One: Turkmenistan. We've been in Turkmenistan less than 24 hours when Glen smashes his head on the diving board at the Hotel Nissa. He was doing back flips - for Geri , who is quickly establishing herself as Stan Trek's most wanted. She's 22, sexy, worthy of back flips, frankly. Glen gets a neat three stitches in the back of his head.

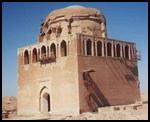

In Turkmenistan, everything is either very old, or very new. In the morning - before Glen smashes his head - we all go to the Tolchuchka Bazaar, a massive open air market in the middle of the desert. Women wear bright purple and gold gowns, men wear flowing white tunics and trousers. Booths sell grapes, adidas sweatsuits, jewelry, tires, and puma cross trainers. It's like Safeway and Target and Track Auto all combined. Only it's outside, 120 degrees, dusty, and I can't understand a word anyone is saying. I stumble around in the heat - until - I find my way to Tolchuchka's highlight: the carpet market. The most beautiful Oriental rugs are draped everywhere, piled messily on top of each other in the dust. The colors are overwhelming. For a moment, I forget the jet lag and the heat and the noise and the color. I buy three carpets from a Turkmen who speaks French with me. He tells me that after the government banned learning languages, he had to take an expensive private tutor. I don't know if I believe him, but, it works, and I don't bargain as hard as I should. Three rugs, 300 bucks - US cash - is not a good deal at Tolchuchka. That evening, the sun still bright, a group of us take the tour bus to the old city Nisa - ruins of the only empire Rome could not defeat. Like most of modern Turkmenistan, it's dust, and for a while, I sit in a dark room and listen. With the desert all around me, I hear nothing - no wind, no people, no life at all - there's only the slight cracks and creaks of a structure resisting 1000 years in the sand. Eventually, I get up and go outside. I share cigarettes with two Turkmen shading themselves behind a wall. The next morning brings Turkmenistan's new: construction cranes and impossibly huge government projects. On every building, every corner kiosk, hang pictures of President Saparmurat Niyazov, a.k.a. Turkmenbasi, "supreme hero of all Turkmen." Turkmenbasi makes Saddam Hussein's penchant for portraits look reasonable. Statues, paintings, photographs, murals. Serious Turkmenbasi in a highly decorated military uniform. Loving Turkmenbasi smiles, wearing a maroon sweater. We drink Turkmenbasi vodka. We photograph this massive tower rising from the desert floor. On top stands - guess who? - arms raised, six times actual size and 24 karat gold. The statue rotates during the day as Turkmenbasi presents the sun to his people.

Ted on loudspeaker: "The situation is you have just experienced your very first militsiya checkpoint. We will have many of these. You may have a false impression that crossing borders is easy, like when we came in, please do not think we're going to get by so easily." Leaving Ashgabod, we see Turkmenbasi's real power: the police state. There is no freedom of movement in Turkmenistan, or in any of the Stans. No freedom of speech, no Bill of Rights. Ted tells of people beaten, robbed, held for weeks with no recourse. Crossing the Karakum, Turkmenistan's "black desert", we pass dozens of checkpoints. The soldiers stop all cars, they board all buses. We drive for hours. We make few stops. We have an itinerary, dammit, and we're sticking to it. The bus's air conditioning fights a valiant but doomed effort against the Karakum's heat, as the temperature hovers around 130 degrees.

Stan two: Uzbekistan. Fifteen hours after leaving Ashgabod, we reach the border - a lonely outpost in the middle of nowhere. It's just after midnight, and the soldiers manning the checkpoint are drunk and tired. Twenty three Americans crossing into Uzbekistan overwhelms them. We walk right through.

Judy: "Here we are, you know, hanging out at the Uzbek border." That's Judy, Ted's wife. It's late, everybody's sleepy, and, well, Judy's kind of pissed off. After the easy crossing, some of our fellow Stan Trekkers are complaining that this whole thing is just too easy. Not dangerous enough.

Judy: "If they want a bad experience, let's engineer it. Let's get someone strip searched. There's your bad experience. "

For me, it's not that there's no danger - the sickness lurking in the food and water freak me out plenty. It's more that I'm not really feeling it. I'm not connecting to the people, the places. I mean, this is Central Asia. Where the hell am I? I'm tired. It's midnight. One hundred and ten degrees. I want a bed. A nice bed. There are very few nice beds in Central Asia.

Ben: "So, tell me your name." I don't remember getting into Bukara, Uzbekistan, later that night. But the next day is beautiful. I wander into the center of town where, outside an old medressa, an Islamic school, built in 1417, I meet Lola and her sister Nadya.

Lola: "Do you understand?" In Uzbekistan, like all of Central Asia, there is nothing to do. Lola's a student - most young people in Uzbekistan are, and for fun she waits for tourists and then shows them around town. Already I've met a lawyer, an engineer, and a teacher who all do the same thing. See, and this is why hanging out with Lola and her sister makes me a little uncomfortable'you know, American being led around by two young and cute local girls. Already sex has become a hot topic. Every hotel bar teems with prostitutes. Sex confronts you in the lobby, in the hallway outside your room, mysterious phone calls at 3:20 in the morning. Back on the bus, Carlos told me this story:

Carlos: "There were maybe around 10, 12 men sitting around and it was 15, 20 women dancing. Men were sitting. Perhaps another dozen women sitting. Yeah. Anyway. Let's just say that principles become negotiable in Uzbekistan. I mean, when an average office worker make around twenty dollars a month, even a little prostitution goes a long way. The guys on our trip - half the guys on our trip - take advantage. So, this morning when I woke up and some people from my group introduced me to a local girl - wink, wink, nudge, nudge - I was skittish. Later meeting Lola and Nadya, walking around town them - in and out of ancient mosques - is great. They're obviously not for sale. But it's a little weird. I really don't know what to think. Beautiful Uzbekistan quickly becomes my favorite country. The people are so friendly and generous. A boy offers - free of charge - to hook two of our group up with prostitutes way out in the suburbs. A few people are actually invited for the much-sought-after, "meal with a local family." After showing me all over Bukara, sharing their bread and grapes, taking me to the walled fortress near the center of town, neither Lola nor her sister will accept even cab fare back to their house. I try to buy them lunch, they say they're not hungry. Ice cream? Nothing. They ride with me back to the hotel and get embarrassed - apologize - when the driver hits me up for a U.S. visa. All Lola and Nadya want are photos. They write me their address and I promise to send them. When they see my Polaroid, their eyes light up. They pose and are beautiful; they have a regal air. I watch them as they clutch the pictures and walk away from me. They laugh and bump into each other and they disappear across the street. The next day we're gone too. On the road to Samarkand. What starts as another blistering hot, and therefore slow, day quickly turns pointed. Central Asia has always been a land of conquests: Alexander crossing the Oxus River, Jengis Khan on his way to Arabia. The group turns first on me, trying to get me to confirm a love affair with the sisters Lola and Nadya. But - when there's nothing to tell, they turn on Frank: we pry from him the story of his rendezvous with "Nozima" late last night. It's a pathetic story, really, yet one he takes great pride in. They meet after dinner. He gets her drunk at the hotel bar, and then sneaks her past the secret police to his room where they share some kind of sexual encounter. He won't say he didn't have sex with her. Instead, he makes lame innuendoes so as not to lose face. But it begs a question: one we've all been avoiding the whole trip. Somehow, this tour has started dripping with sex. At one point, Ted admits he actually chose participants based upon who on the bus would hook up with whom. During one stretch, a few of us go through the entire group pairing people off.

The question we've been avoiding is this: given man's "propensity to covet thy neighbor," can you have sex in Central Asia, without harming the Central Asians? Or, maybe the better way to ask that is, if you are going to s'''' them, can you do it in a such a way that it doesn't sting for too long? The debate here is between Frank and Carlos. Before we left, Frank went on the Internet and corresponded with ladies in a number of different cities we'll be visiting. He says he's trying to get to know some of the locals, but the rest of us, we think we know what he's up to. Carlos, on the other hand, makes no bones about buying sex, wherever it's available. Who is more exploited? The woman giving it up for free - naively hoping for love, happiness, I don't know, a visa maybe? - or the prostitute who knows exactly what's going on? It's a tough question. It's tough to ask and even tougher to answer. Maybe you can't. Maybe you have to deny attraction, deny man's "propensity to covet thy neighbor" when you travel. Deny part of being human. But on this hot day in Uzbekistan, as I said, on the road to Samarkand, no one is answering it - or even trying to - because nobody has asked. A woman gets mad, outraged even, as she listens to Frank's story, but by the end of the day she's apologizing to him, apologizing to all the men on the bus. "I over-reacted," she says, fanning herself. "I don't know what came over me. "Maybe it was the heat." To be honest, it was a mistake. Late in the afternoon, the bus pulls into Samarkand. We pile out at the Registan - this incredible complex of mosques linked by 300 foot facades, covered in tiny mosaic tiles. It's an architectural marvel. Deep cobalts, bright yellows, pictures of tigers, calligraphy. Inside, we get caught up. Paul, Carlos, and me, we get carried away listening to man play music. Afterwards he invites us to a performance, a play set in one of the many courtyards inside the Registan. It's cool - relatively - as the sun is starting to set. We watch actors in colorful silks and a tale of forbidden love discovered. Not quite Romeo and Juliet, but, still, Uzbek Shakespeare. Afterwards we leave and go back to the bus. Now, we hadn't exactly "asked permission" to watch the play. We told the others and most said, okay. But as it turns out, it's just what "our fearless leader" was waiting for.

Ted: "So, for you I hope, you had a good concert, but you're assholes. You had six fun hours and the rest of us had 18 stupid hours. That's going to end righ here. We had an experiment in democracy, that's going to end. Democracy doesn't work. We will now go to Turkmen model. Tedmenbasi will dictate the schedule of the bus. The days for the autark have returned. For that, I am grateful." So, Tedmenbasi, as he's called now, tells us when we eat, when we depart each morning.

With word from on-high, we drive the bus to dinner. The atmosphere is dreamlike - water flows everywhere in Samarkand, incandescent lamps light the tree-lined stree ts in front of us. It's midnight when I get back and my room is too hot to sleep. I crash outside and think cheesy poetic thoughts about sleeping under the stars in Samarkand. I feel like Whitman - or Wilde. The next morning there's a panic. Carlos didn't come back last night. Nobody knows where he is. He was last seen at the restaurant, courting local Russian girls. But, the rule of Tedmenbasi is rigid and severe. We wait until 10 o'clock, the appointed hour of departure. We load Carlos's stuff on the bus and prepare to leave him. We get on-board and go. At 10:15 we find Carlos. One of the Russian women brings him back to us. On the bus, Ted leads the interrogation.

Carlos: "I was at somebody's house. How many saw the girls last night? How were they?" We're not going to find any answers here, not on this bus and not on this trip. In fact, this whole issue, this whole story line that I've been running down is soon going to disappear and not raise its head again. See, we're now on our way to Tashkent, the de facto capital of Central Asia. with 2.5 million people. In 12 hours we'll be there. Tomorrow, we will forget what we've been discussing, forget what we've been fretting about. This happy-go-lucky side of our trip is coming to an end. Tomorrow, we'll be in Tashkent, and tomorrow - the sickness begins. Backannounce: At its conception, Ben Adair's trip was divided in two: the soft and easy half, and the tough and dangerous half. Tune in next week to hear the treacherous side of the story, including why never, ever to eat Mexican chicken at Czech restaurants in Almaty, Kazakhstan.

|

| American Public Media Home | Search | How to Listen ©2004 American Public Media | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy |