|

|

|

|

|||

|

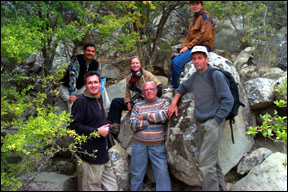

Feature: The Lost World of Pomegranates I am in southern Turkmenistan, near the Iranian border, on a moonlit evening. Two guards are arguing about my passport. I have spent six hours driving across the desert with seven people I've just met - two Uzbeks, three Turkmens, a Tunisian, and an Italian. I have arrived at this lunar landscape that passes for a border post on a whim. A few months ago the Italian told me some of the most fantastic travel stories I have ever heard. And I'm a sucker for good travel stories. I met Stefano Padulosi last spring. I was seduced by tales of startled elephants in Swaziland, and the car-swallowing mud of the Congo's rainy season. And of course, his story about the first time he camped outside in Zimbabwe, when a pack of angry lions approached his tent. But the concern increased... He survived the lions, the mud, and the elephants...but he is not your average Indiana Jones wannabe. Stefano is a plant explorer, wandering the world to collect food plants with rare and remarkable genes. He is a kind of crop conservation crusader. He invited me to join him on this mission, searching for pomegranates in Turkmenistan. Now pomegranates never meant much to me. I thought of them only as pretty red fruits that were hard to eat. But they mean a lot to many other people. They appear in nearly every painting in Turkmenistan. They are a symbol of fertility in the arab world. Their leaves are used to treat malaria in norther Thailand, and their shape and original name - granat - are the basis for the deadly hand grenade. But even the real fruits are hardy, I soon learn. They grow out of rocks in the desert! Stefano has come to meet Dr. Levin, because he knows more about pomegranates than anyone else in the world. He tends to a collection of 1,117 pomegranates from seven different countries, each one with unique genes. While this collection once attracted handsome funding from Moscow, Kara Kala has now become a backwater with the Soviet Union's collapse. The institute's budget has dried up, and Dr. Levin's collection has been orphaned. But the birthplace of pomegranates is like the center of the world for Messoud Mars, a pomegranate expert who came all the way from Tunisia. Mars: "I mean, my dream is now a reality. I always think about this wild population of pomegranate and getting to collect plant material. Now I'm doing that! I'm very happy."Not exactly a close encounter with wild elephants or angry lions - but Stefano says, for a plant explorer, it's even better! Stefano: "It's the dream of every plant explorer to reach the center of origin of his crop."Having captured the rare, wild pomegranates, we head back to Dr. Levin's house. It's nestled among grapevines, rosebushes, and persimmon trees. It's filled with books, journals, manuscripts...a kind of monument to pomegranate scholarship. Dr. Levin brings us pomegranate wine, walnuts, and fresh fruit while his wife Emma picks dinner from her garden. While it's all very romantic, I'm still waiting for something to happen. Waiting for the sense of adventure I felt in Stefano's tales. The next day we pile back into the old Soviet van. The road ends at the top of a dusty hill, overlooking an absolutely silent ravine. Dr. Levin leads us down a footpath, past turtle shells and discarded porcupine quills. Suddenly we enter a ravine filled with lush green treed and verdant grasses.

Stefano: "So we are now sitting in one of the most important centers of origin of major agriculture crops. For pears, apples, figs, pistachios, pomegranates, and many other vegetables."It seems we have entered a mythical wild garden. All around us are fruits, berries, nuts. Stefano: "Ah, there are some blackberries...big berries...mmmmmm. They are immagure, but the mature ones are very nice..." Levin: "Wild Grape!" Stefano: "Great! Fantastic...I have never seen wild grape!"The flavors are unbelievable - more intense than anything I have ever tasted before. Then we realize that the ground is covered with salad greens. Stefano: "This is a very widespread population of rucola, ruca sativa...which is rocket in English."We make ourselves handfulls of impromptu salad...throwing in the occasional wild sorrel to balance out the spicy arugala. I love this...you don't know how much! Finally, I've found what I came for. Not necessarily the thrill that comes from surviving personal danger, but the thrill of experiencing something that is so rare, so singular, that it pierces your everyday perception of things and brings them into sharper focus.

Stefan: "I think this is feeling like a paradise."And Dr. Levinson explains that there is danger here...not to us, but to the pomegranates and the wild things we have found here. He says that local herders are now bringing their sheep and cattle to these ravines, which is slowly killing the wild orchards. Even Dr. Levin's beloved collection of trees is starting to die of thirst as there is no longer money for irrigation. He's retired now, and no one will take his place. That is why Stefano brought us here. To tell tales of this place to the outside world. To bring funds back to this place, to avert the total loss of these things. I hope it works, because while pomegranates may not have meant much to me before, I can now see them as Turkmens do...as Dr. Levin does...as sparkling rubies in this dry place. On the trip from Kara Kala back to the capital of Ashgabad - even as the memory of that fruitful ravine shimmers in my mind - Turkmenistan offers up one more gem...a real traveler's tale. Messoud and I are detained by police in a small desert town called Behardeh. There is a problem with our passports. They have been sent to the capital to extend our visas. So we are held by the police, heirs of the KGB and the Soviet bureaucracy for six hours. We are released only when one of our Uzbek companions retrieves our passports from the capital and saves us...from dying of boredom in the police station. Maybe not elephants or lions...but Stefano was amused. For the Savvy Traveler, this is Anne Marie Ruff in the hills of Kara Kala, Turkmenistan.

|

| American Public Media Home | Search | How to Listen ©2004 American Public Media | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy |