|

|

|

|

|||

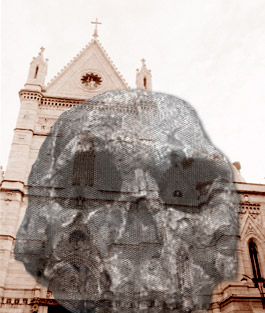

Napoli Purgatory By Frank Browning 10/25/2002 My friend Guido will probably die in Naples. His family has been dying there for centuries. Guido runs an elegant paper shop beside the Corpo di Napoli. Corpo di Napoli: The body of Naples. It's a marble statue in the form of Neptune, right on the Spaconapoli, the long central street in the core of the ancient city. A lot of people, including the late Marcello Mastroianni, known for his beautiful body, loved Naples for its corporeality, the intense physicalness of a city that celebrates everything about the body: its sounds, its aromas, its agility, its lust, its evanescence, and finally, its crystallization -- or as the Neapolitans say, its mineralizacione: Its bones. For years, I'd walked past a baroque church just a couple blocks from Guido's place, a church featured in many tourist guides because of the bronze skulls mounted on the iron railings at its entrance. Santa Maria del Purgatorio ad Arco, the church of Purgatory by the Arches. It is here beneath the ancient sooty arches that the bodies of the living -- hawkers of everything from glistening trout to spiny artichokes to contraband cigarettes -- commune with the spirits of the dead, housed deep in the crypts of the Congregation of Purgatory across the street. It wasn't so long ago -- the 1970s -- that daylong, ecstatic masses were held here in the Purgatorio ad Arco -- not in the main church with its famous paintings and baroque statuary, but in a second church below ground that now stands empty. From that underground chamber, celebrants would descend into yet a third lightless vault, where the bones are kept. Guided by messages that had come to them in their dreams, they would pick up a femur, or a finger, or a breastplate, carry it upstairs, then clean it and pray for the redemption of its owner's soul. Guido: We have the culture of the dead. Guido tells me this as we descend. The room is vast, empty except for the echoes of our voices and, of course, the bones. Small piles of human bones set in niches along the walls. Guido: When someone died, he wasn't dead, of course. We expect something. That "something" the Neapolitans expect is called "purgatory," that place where souls who were not altogether bad might go and simmer a while in the flames, and, there, be purified or purgated before floating up to heaven through prayer and the grace of -- who else -- La Madonna. And so, this church, the Madonna of Purgatory, where the souls of the dead could speak to the living. The story of Naples is so full of the dead, Guido goes on. The dead of wars, of plagues, of earthquakes, of Vesuvius hovering against the horizon. The dead are always around, if not altogether present. Guido: You have the dead every day. It's a tradition that is difficult to lose because every day you have the died. We have the tradition -- if don't have tradition, it's like in Africa. Look at dead as part of the life: exactly the same. All this death and disease turned the Neapolitans into a wily lot, so that even prayer took the form of a sacred wager. Guido: You pray purgatory soul because they can give you Latina. Do ex deus: I give you something, I expect something, tit for tat. This is the tradition here. I pray for a soul I don't know, a bone I don't know, but because I am a good man, I expect something. You pray for the bone and the soul that is still attached to it, and in exchange, that wandering soul can do you favors: advise on a business deal, tell you if your daughter's marrying the right boy, warn you not to take a certain airplane flight, and most often, offer tips on a good number in the lottery. What all this means, of course, is that a bone is not just a bone. Salvatore Saleme: To adopt a dead bone, it gives you buona fortuna, good luck in life, makes you feel better. You feel it like something positive. It's just a way to make you feel better. Salvatore Saleme tends bones for a living. He runs a funeral service. The cleaning of the bones is an important part of any Neapolitan funeral business because when you're buried in Naples, it's only for a little while. When you die in Naples, your body will not be embalmed. It will be wrapped in a shroud or dressed in a silk or linen gown, then placed in a coffin with holes drilled in the bottom, so the fluids of the putrefying flesh can drain off quickly. Salvatore: After 2 years, 3 years, they take out the coffin -- what remains of the coffin -- they put the bones, the remains, in something like a box in the wall. They start to really take care of the bones. You see some old women go to the cemetery and they ask the people in the cemetery to open the box -- and they start cleaning the bones, touch them, to really take care of them. To hold the skull of your dead husband or son to your face, to bathe it in naphtha, to draw the knobby brow lightly to your lips -- well, even if the local health department in Shaboygin agreed, you might not want to do it under the noonday sun, where the neighbors could watch. But if you come here in November and visit one of the city's many cemeteries, you'll easily find people taking out their loved ones' bones, cleaning them with soft white cloths, and returning them to their engraved bronze storage boxes. It's all, Salvatore Saleme says, an affirmation of the unbreakable tie between body and spirit. Salvatore: I think the body is still the spirit. So, when you take care the body, you still take care of the spirit, and so the dead people. This makes you think that life goes on forever. In another way, but you can live forever. As Salvatore says, this is not exactly a Christian idea, the continuing presence of the spirit in the decaying flesh. No, not at all, agrees Patricia Giordano, a journalist and sometime anthropologist who writes about the death rituals of the Neapolitans. Patricia: speaking Italian It was the Romans who mixed the bones of the dead, especially dead warriors, and then held feasts to celebrate the collective passage of their spirits. Speaking through her, British collaborator John Percherd, Patricia Giordano says the church has long wrestled with the ancient pagan customs that persist throughout southern Italy. Patricia: speaking Italian Signs of the Neapolitan death cults are not hard to find. Besides Sunday visits to Santa Maria del Purgatorio ad Arco, flyers for the newly dead punctuate the warren of tiny streets nearby, the scant sunlight filtered by exhausted clotheslines bearing sheets, shirts, and underwear. John Perchard and a friend take me on a walking tour through a worker's district just behind the National Archaeological Museum. There are the usual shrines to the Madonna and sundry saints you see all over Italy, but then we step around a corner and come upon something a bit spookier: a small box hollowed out of the wall, the figures inside lapped by flames, lit with red lights. These grim shrines, called Anime di Purgatorio, or Spirits of Purgatory, are peculiar to Naples. John: In all, there are 6 figures represented. One is of Christ on the cross. Then, there's the Madonna. The other four figures are the priest, the lost woman, this man is the pimp of the lost woman, and then there's an old man on the other side of the cross. And, here, the flames are made out of wood with some flames painted in the background. That's right: A whore, a pimp, an old man, AND a priest -- all toasting in purgatory. John: Since he is human, he is in touch with sin, and so he is also in the flames, but he also acts as an intermediary as well, as he can for the other lost souls, but in fact, around the Virgin Mary, there are no flames. All these images of flames and suffering might seem much more appropriate to the fire-and-brimstone preaching of Pat Robertson than to the infamously lusty, passionate Neapolitans. But then, John reminds me, the flames of purgatory are not about Hell and damnation. Indeed, every Neapolitan I've ever spoken too shrugs his shoulders and laughs at the notion of hell. John: The Neapolitan people believe that hell is a simple representation of life on earth, and that you can't really go to hell because you are living in hell. Purgatory is the only possibility because hell is something they've already experienced. And, so, to pass by the these burning shrines, to visit the bone box at the cemetery, to descend through the baroque grandeur into the lower regions of is not about suffering demons or damnation. To stroke the bone is merely to commune with spirits past whom, sooner rather than later, will become your eternal companions. For The Savvy Traveler, I'm Frank Browning.

|

|

Search

Savvy Traveler

|

|