|

|

|

|

|||

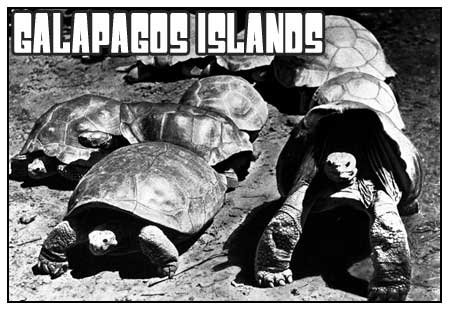

Sea turtles are amongst the island's many fauna and flora.

Galapagos By Jeff Tyler 12/06/2002 The nautical alarm clock signals a new day, and a new island. We're aboard an 80-foot yacht, in accommodations far less glamorous than the word yacht would imply. But the boat is home base for 16 of us as we wind our way around half of the 13 major islands that make up the Galapagos.

We tread carefully around the algae-covered tide pools where marine iguanas nap in the sun. As they evolved in this arid equatorial landscape, the endemic marine iguanas learned to eat underwater. They can dive beneath the waves for an hour. These traits exist only in the Galapagos. That's what fascinated Darwin: how species adapted to survive here. Like the finch that went vampire, and lives by drinking blood from another bird's elbow. Even introduced species have adapted...like the feral goats.

Naturalist-guide: "It's hard to believe, but after 20 years, the goats from Santiago Island, they are able to drink seawater -- a little water, but enough to survive."That's our naturalist-guide. Every tour is required to have one. In this very-controlled environment, the guide is part teacher, part traffic cop. Although the national park consists of almost 2 million acres, most of that is out-of-bounds. The distance we're allowed to cover in a day is roughly equivalent to walking around a city block three times. And, there are plenty of other rules: You can't bring food or pets or plants to the islands; you can't take anything from the islands; and, don't even think about touching one of those cuddly baby sea lions. Naturalist-guide: "Remember, don't touch him. And, stay one meter from the little one. Somebody touch a baby, the baby will be rejected by the mother."

Back on the boat, Stella, a 31-year-old Norwegian backpacker, raves about swimming with sea lions. Stella: "That was just really, really incredible. They're really, really huge, and they come sliding around you, over you, on your side, and they come straight at you, towards your mask -- and just when you think they are going to hit you, they go to the side."That's the kind of "once in a lifetime" interaction with wild animals that gets tourists so excited about the Galapagos. In fact, these creatures have been captivating visitors here for centuries. But with the publication of "The Origin of Species" in 1859, Darwin made the Galapagos famous. Ed Larson, the author of "Evolution's Workshop," says the job of protecting this fragile habitat fell to future generations. Notably, a British biologist named Julian Huxley. Ed: "Now, Julian Huxley was a visionary, and he believed that if people could get closer to nature, they could have a sort of evolutionary epiphany, where they would realize that we are all creatures living on one world and we need to share and work together."Huxley worked to develop a new kind of tourism: one that could educate, preserve natural resources, and promote new economic rewards through conservation. It's what we now call "eco-tourism." In 1959, Ecuador laid the groundwork when it declared 97 percent of the Galapagos islands a national park. Huxley's idea that tourists would sail around with naturalist-guides didn't become reality here until the 1970s. Today, 80,000 people travel to the Galapagos each year. Studies show the direct impact of all these tourists on visitor sites is negligible. The management of the national park has won international recognition, and its policies are widely imitated. But outside park boundaries, the success of eco-tourism is less clear. The Galapagos has a permanent population of around 17,000. Most of those people live here, in Puerto Ayora. Just 20 years ago, this was a sleepy little fishing village without television and only sporadic electricity. Now, it's got Internet, ATM machines and a FedEx office.

In the past 2 years, two ships have run aground in the Galapagos, spilling over 200,000 gallons of fuel into the sea. That fuel was meant to sustain tourist boats and the local economy; instead, it killed 60 percent of the marine iguanas on one island. That bothers Daniel Fitter. A lifelong native of the Galapagos, Fitter works as a guide and makes a good living. But he worries about a runaway tourism industry, forever upgrading to newer and bigger boats. Daniel: "And, those things are bound to have secondary impacts: bigger boats, more fuel consumption, more oil pollution, more rubbish being thrown away. And, just the silliest things -- like cameras now work on lithium batteries -- and now, thousands of people come here; they bring thousands and thousands of lithium batteries to the Galapagos. Thousands and thousands get chucked in the rubbish bins and in the landfill here on the island -- and who knows what happens after that."What happens next isn't on most people's minds here. They're too concerned with making a living now. Puerto Ayora's population has tripled in the past 10 years, as Ecuadorians flocked here to escape the wretched economy on the mainland. But many newcomers lack education and English skills, so they are unqualified for well-paid jobs in tourism. At the same time, some locals complain that their livelihoods are being threatened by national park restrictions, such as quotas placed on threatened species in the marine reserve. Fisherman (in Spanish): "Aqui, un animal vale..."This fisherman says that, in the Galapagos, "An animal is worth a lot more than a human being. Here, one tortoise, one bird, one sea lion, has more value than a human baby." In recent years, fishermen have rioted, sacked the national park offices, and even held tortoises hostage until certain fishing quotas were abandoned. As local hotel owner Jack Nelson sees it, such conflicts are nothing new -- and they are not limited to the Galapagos.

Jack: "It's something that has been recognized in wildlife parks throughout the world, in Africa and so on. It's that, if the local population doesn't feel that they have an investment in it, they don't feel like there is something in it for them, then the notions of conservation and biodiversity, and so on, is meaningless."Puerto Ayora lies outside the park's jurisdiction, but park officials recognize that a local community that feels neglected poses a threat to conservation. So, they've taken initial steps to help steer more tourist dollars into the local economy. But guide Daniel Fitter questions this strategy. Daniel: "Yes, I got the wonderful letter from the park service a couple of months back that said I had to make sure my passengers spent a minimum of 2 hours in Puerto Ayora to have time for shopping. And I thought, that's a bit ludicrous considering that if my passengers don't want to spend 2 hours shopping in Puerto Ayora, I think they have a right to refuse it." It's questionable whether more tourist spending could alleviate the problems here. Bigger profits might just accelerate development, while the tough issues, like education and under-employment, won't go away just because sales are up for souvenir T-shirts. Several decades in, eco-tourism in the Galapagos is still evolving. Julian Huxley's ideas seem to be working, as far as education and preservation go. But ultimately, it may be that third leg, economic development, that saves or destroys this ecosystem. Still, there is good reason to be optimistic. In this barren landscape of volcanic rock baked by the equatorial sun, the example has been set by pink flamingos, blue-footed boobies and penguins, all of which have been able to adapt and thrive here. Surely, it can't be impossible for humans to adapt. In Puerto Ayora, Galapagos, I'm Jeff Tyler for The Savvy Traveler.

|

||

| This feature comes from HearingVoices.com, funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the National Endowment for the Arts. |

|

Search

Savvy Traveler

|

|